Residents of Clifford’s Inn are also fortunate to live in an area of huge historical importance with many local places of interest that have connections to people and events over the years.

For seven centuries there has been a Clifford’s Inn.

In 1310 the land on which Clifford’s Inn stands came into the possession of the first Baron Clifford. It was an unremarkable London landholding of one of England’s most powerful families, situated outside the walls of the City of London to the west of Faitour Lane, a noun which Chaucer uses to mean “beggar” or “odd jobber”. Quite what use the first baron and his sons made of the land is not recorded. After the death of the third baron in 1344 it fell to his widow, Isabel, to administer his estate. For the sum of £10 per annum, she granted use of the land to the first ever Inn of Chancery, a society providing initial education for young men seeking admission to one of the Inns of Court. The fortune of the area was on the rise, and in 1394 Clifford’s Inn was included within the boundaries of the City of London.

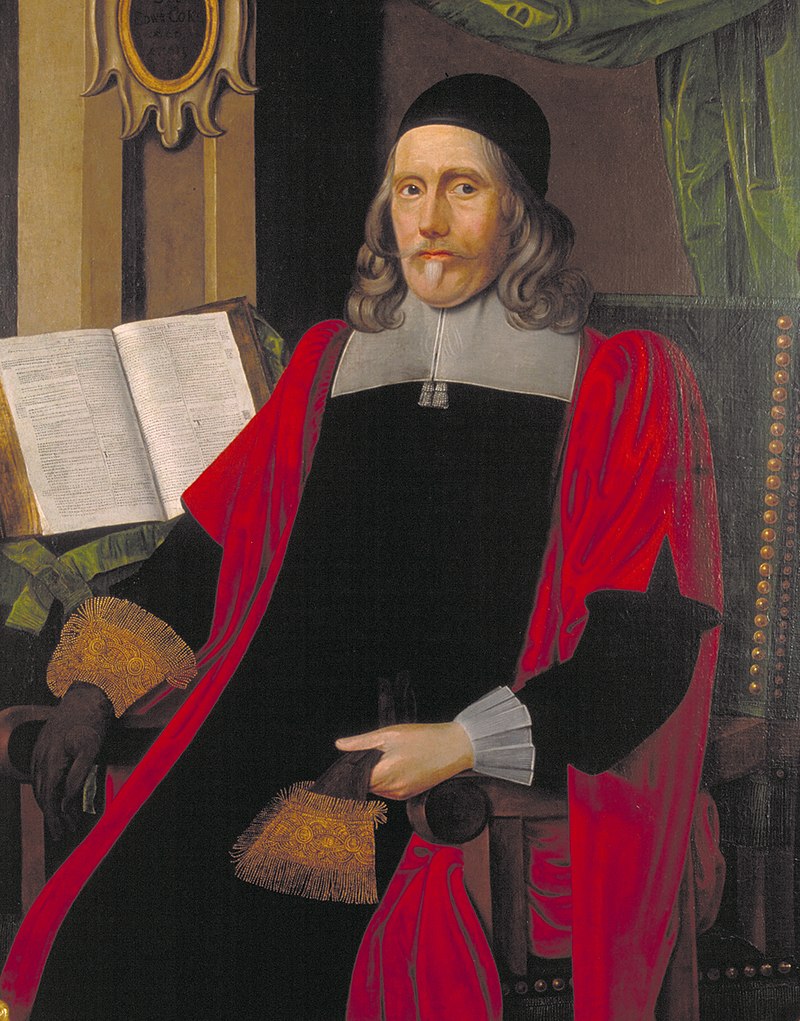

Clifford’s Inn of Chancery existed as a society from 1344 to 1903 providing a “habitation” for aspiring lawyers. Buildings on the site were added and replaced throughout the period. Sir Edward Coke was a member, becoming the outstanding legal brain of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, and the author of the statement “A man’s home is his castle – for where shall he be safe if it not be in his house?” John Seldon was also resident, acclaimed by John Milton as “the chief of learned men reputed in this land”. Very many famous lawyers and City politicians have had connections with Clifford’s Inn.

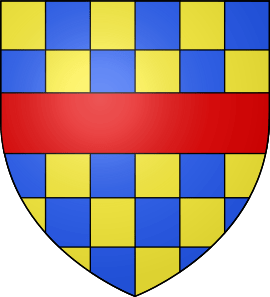

Ownership of the freehold passed in 1618 from the Clifford family to the Inn itself, though retaining the name Clifford’s Inn. The coat of arms of the Clifford family continued to be used by the Inn and today are still displayed outside. The primary access to the Inn was then from Fleet Street through Clifford’s Inn Passage, though with exits both to Fetter Lane and Chancery Lane. Residents endured the Great Plague of 1665, but in the following year Clifford’s Inn was just outside the area destroyed by the Great Fire of 1666 and escaped unscathed. Subsequent to the Great Fire it served as the location of the court settling the hundreds of post-fire City land disputes.

Clifford’s Inn developed its own eccentric traditions, presumably reflecting the youth of those then living here. Bread for formal meals at Clifford’s Inn was baked in the shape of a cross. At the start of a meal the Principal took four such loaves, and after saying Grace dashed them three times on the table before distributing the bread by throwing it the length of the table. This tradition, which appears to have started in the eighteenth century, continued through the nineteenth century.

The nineteenth century saw constructed the Gate House on Clifford’s Inn Passage. It is from about the 1830s and in a style which evokes a previous age, complete with battlements. It is attributed to Decimus Burton, an outstanding architect of the Victorian Age, who in his youth had himself been a resident of Clifford’s Inn. About the same time the mediaeval church of St Dunstan in the West was demolished and the present church constructed on the site. Clifford’s Inn came in the nineteenth century to be the home of men in professions other than law, and men of more mature years. It developed a mixed residential and business character, with the same rooms serving as residence and business premises. Samuel Butler, Utopian novelist and philosopher, was for many years resident in Clifford’s Inn, and it is here that he wrote his two best-know novels, The Way of All Flesh (1864) and Erehwon (1872) as well as his translations of The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Charles Dickens provides glimpses of Clifford’s Inn in the nineteenth century. The building is named in four of his novels: in Pickwick Papers a body is found by a new tenant concealed in a locked cupboard in a flat, in Bleak House Melchisedek has chambers here; in Little Doritt Edward Dorrit (Tip) languished as a clerk here for six months; in Our Mutual Friend it is a “quiet place” for John Rokesmith to speak with Noddy Boffin. Dickens frequently described real London scenes in his novels without naming them, and it is likely that Clifford’s Inn is described in other Dickens novels. The idea that it is in Clifford’s Inn that Dickens envisaged Scrooge living (in A Christmas Carol) seems hard to prove, though there is a puzzling reference in the story to St Dunstan, which may suggest proximity of Scrooge’s home to the church.

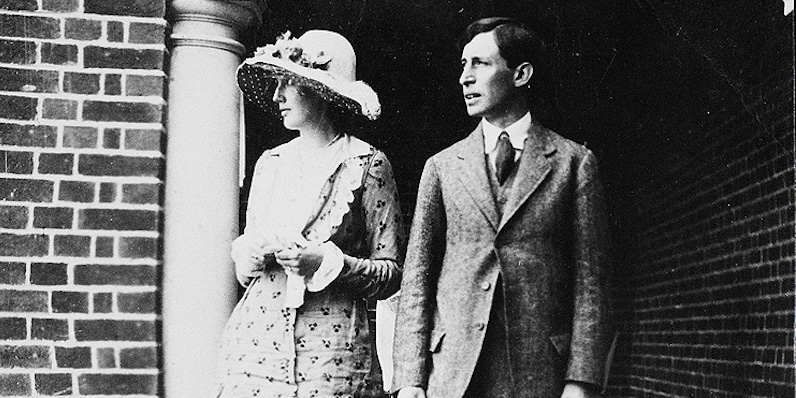

Following the 1903 dissolution of the Inn of Chancery, the freehold of Clifford’s Inn was sold in two lots. A smaller part adjacent to Chancery Lane became in 1910 the site of an office building, now 5 Chancery Lane. The larger section, containing most of the long-standing buildings of Clifford’s Inn, continued to be used for mixed commercial and residential purposes. It became home to organisations including Society of Women Writers and Journalists, London Typographical Society, London Positivist Society and Art Workers’ Guild. Apartments within the building continued to be occupied by people working in law, but additionally are found photographers, tailors, architects, and artists including both painting and sculpture. Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard Woolf lived at Clifford’s Inn 1912-1913 in flat 13, becoming residents immediately after their honeymoon. It is here that Virginia Woolf wrote much of her first novel The Voyage Out.

Most of the old buildings of Clifford’s Inn were demolished in 1935, replaced by the 1936-7 building of serviced apartments above offices. Flats were typically of one or two rooms. It was envisaged that residents would mostly eat in a communal dining room or have meals brought to their rooms, a system facilitated by the provision of a dumb waiter. The flats were built with fireplaces and chimneys (subsequently removed) and lit by gas, with a tiny kitchenette including a gas burner. The building is one of the few survivors in Fetter Lane of the Second World War blitz on London. Many notable individuals have lived in the building which is the present Clifford’s Inn, including Lord Denning who was resident in the 1970s.

The Fetter Lane façade was replaced in 2014, the new one designed by Gibberd Architects, and clad in Portland stone and Carrara marble.